Why Health Officials Warn: Avoid Eating Fruit Bitten by Bats or Birds to Reduce Nipah Virus Risk

Imagine reaching for a ripe mango or guava at the market, only to spot small bite marks or signs of gnawing—something that might seem minor or easy to overlook. But with a recent cluster of Nipah virus cases confirmed in India’s West Bengal state, health authorities are highlighting how these tiny signs on fruit can pose a real concern. The virus, carried primarily by fruit bats, often spreads through contaminated produce like partially eaten fruit, and simple everyday checks can help minimize exposure during these periodic alerts.

What many people don’t realize is how common transmission routes tie back to familiar foods in tropical regions. The reassuring part? Prevention relies on practical, no-cost habits that fit right into daily routines. Keep reading, because later we’ll cover the most straightforward food-handling tweak that experts emphasize as a strong, everyday layer of protection.

Understanding Nipah Virus and the Current Concern

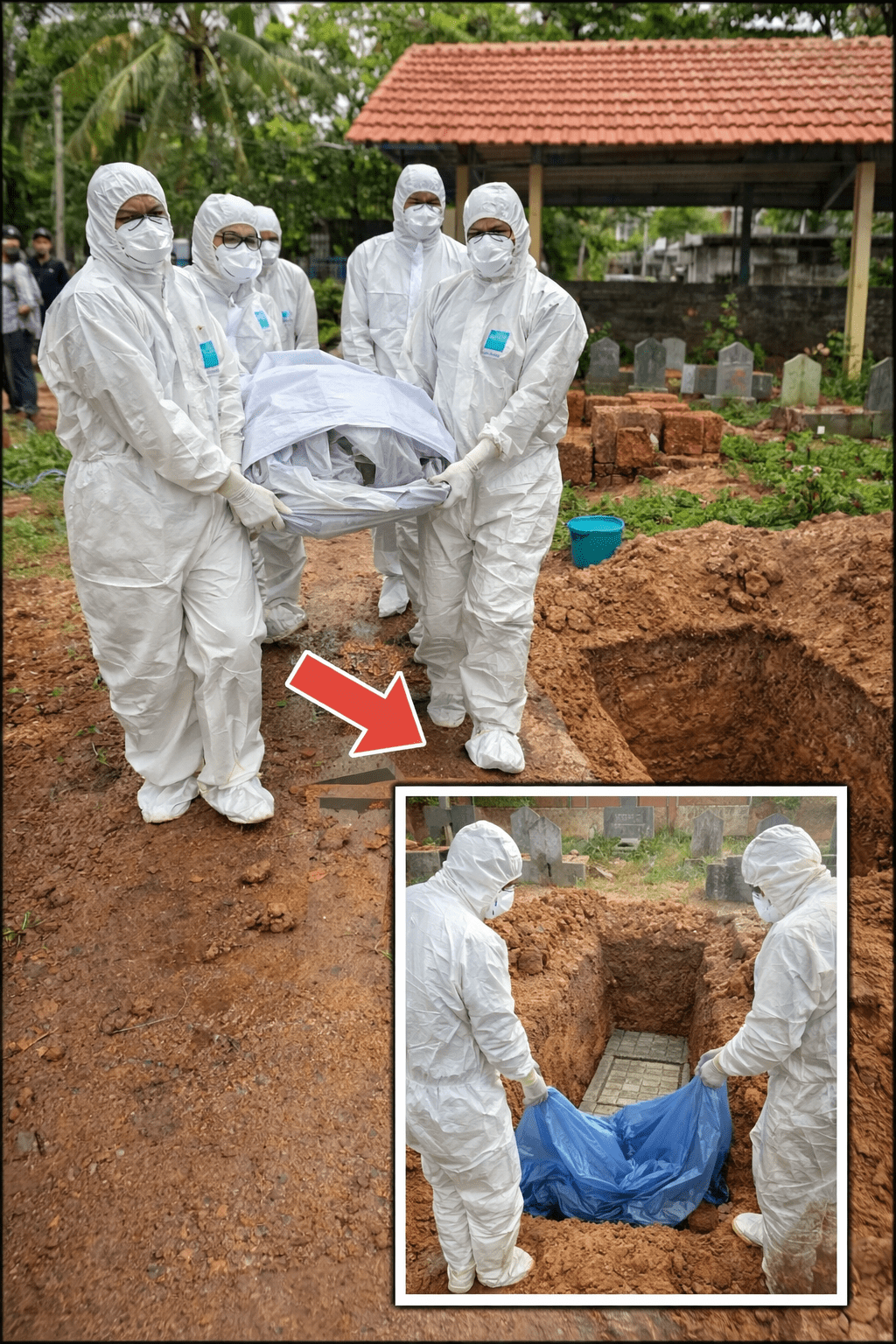

Nipah virus is a zoonotic pathogen—it jumps from animals to humans—and was first identified in Malaysia in 1999. Fruit bats (flying foxes) serve as its natural reservoir, with sporadic outbreaks occurring mainly in parts of South and Southeast Asia, including Bangladesh and India.

The World Health Organization (WHO) notes that Nipah infections can cause severe illness, with reported fatality rates ranging from 40% to 75%, varying by outbreak and access to supportive care. No vaccine or specific antiviral treatment exists yet, making prevention the primary strategy.

In late 2025 into January 2026, India’s West Bengal state reported a small cluster: five suspected cases (mostly healthcare workers at a hospital near Kolkata), with two confirmed positive. Contacts were traced, tested negative, and no broader community spread emerged. India’s health ministry clarified only two confirmed cases since December, with enhanced surveillance containing the situation. Nearby countries like Thailand and Taiwan increased airport screenings as a precaution, similar to past global health responses.

The key takeaway: while outbreaks remain limited and rare globally, this event underscores the importance of awareness around common transmission pathways.

How Nipah Virus Typically Spreads—and the Fruit Connection

Transmission isn’t as casual as many respiratory viruses, but when it occurs, it can be significant. Primary routes include:

- Contact with infected animals, especially fruit bats or, in some past cases, pigs.

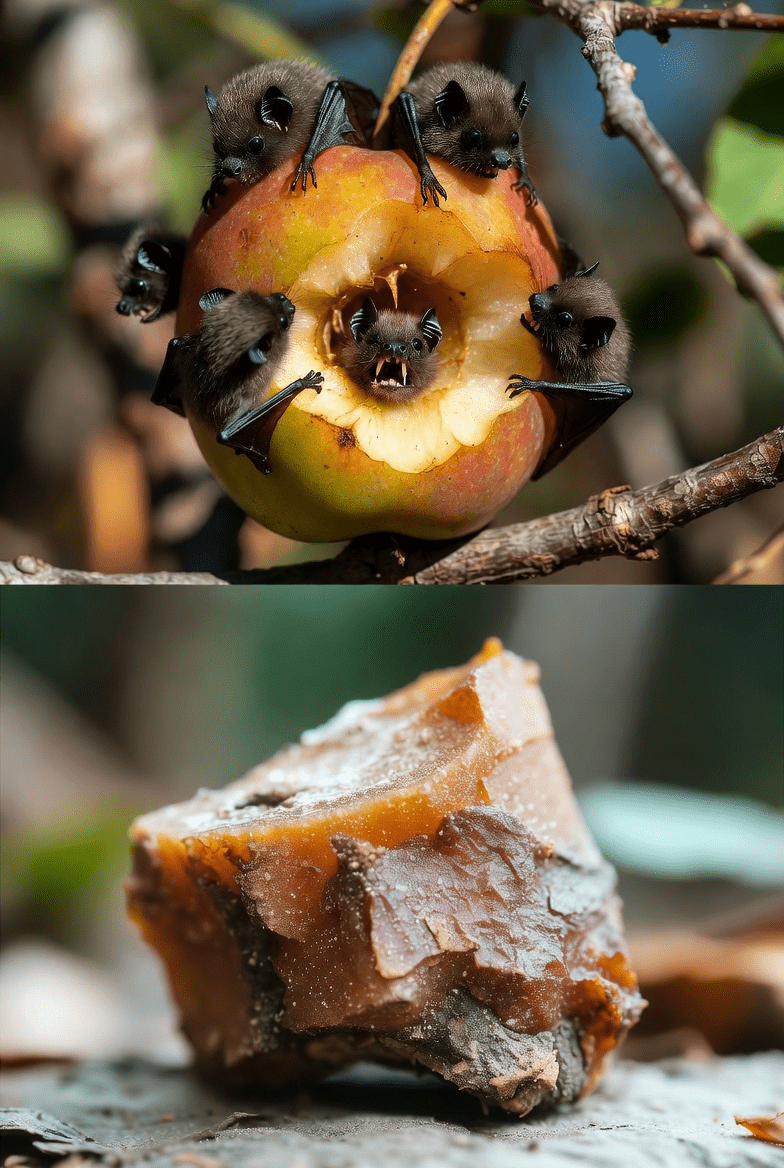

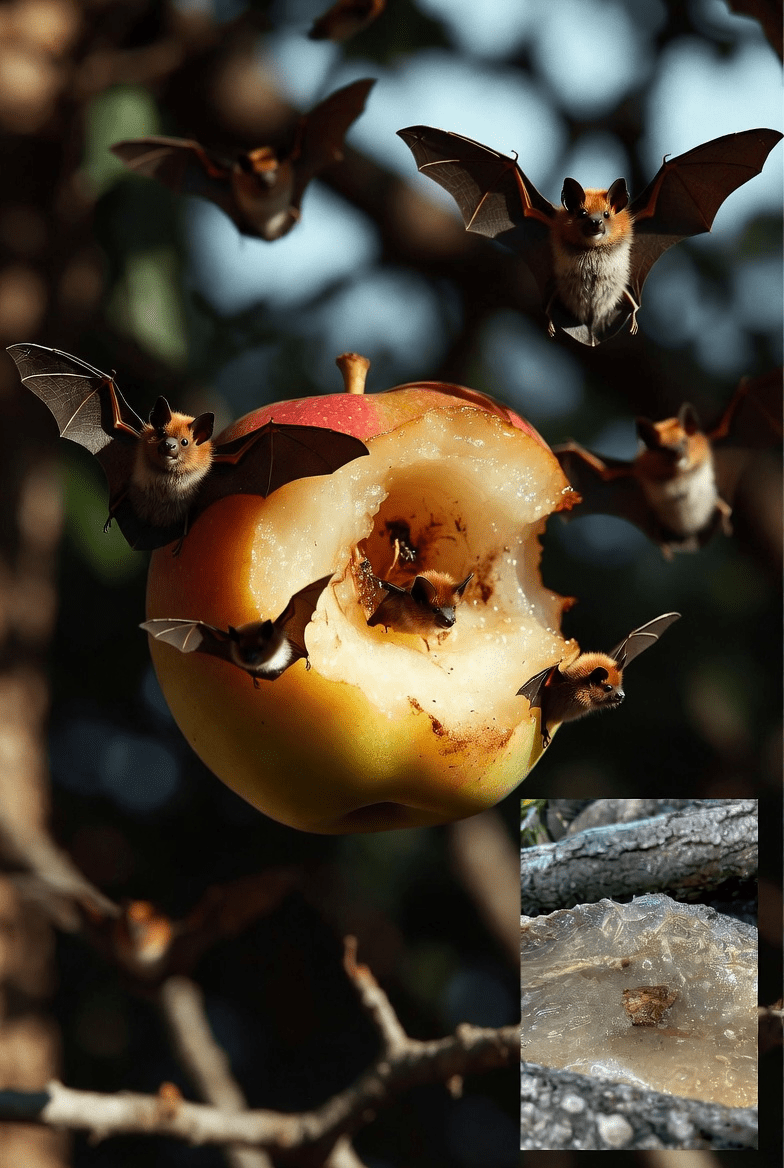

- Consuming food contaminated by bat saliva, urine, or feces—often raw date palm sap or fruit partially eaten by bats.

- Close person-to-person contact through bodily fluids, particularly in caregiving or healthcare settings.

But here’s the interesting part… Fruit bats frequently feed on ripe fruits on trees or fallen ones, leaving saliva or bite traces. In areas where mangoes, guavas, jackfruit, or similar fruits are staples, this creates a potential exposure if items aren’t inspected carefully.

Health bodies like the WHO and U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) stress that avoiding visibly contaminated produce has proven effective in reducing spillover risks in affected regions.

Recognizing Symptoms and Why Prompt Attention Matters

Symptoms generally appear 4–14 days after exposure (up to 21 days in some cases). They often begin mildly, resembling other common illnesses:

- Fever

- Headache

- Muscle aches

- Vomiting or sore throat

In severe instances, progression can include dizziness, drowsiness, confusion, seizures, or encephalitis (brain inflammation). Survivors sometimes experience lasting neurological effects, such as persistent seizures or personality changes.

The truth is… these flu-like early signs can delay recognition without exposure context, like travel to outbreak areas or contact history. Health guidance urges: if symptoms develop after potential risk, seek medical evaluation quickly, avoid close contact with others, and share relevant details with providers.

Actionable Prevention Steps from Health Authorities

Here are practical recommendations drawn from official guidance—easy to apply right away:

- Prioritize food safety basics: Wash fruits thoroughly under running water, and peel them before eating. Opt for “eat cooked, drink boiled” where possible.

- Check fruit carefully: Avoid any with bite marks, gnaw signs, tears, or damage from animals like bats, birds, or rodents—even small imperfections warrant discarding.

- Skip unprocessed tree saps: Avoid raw date palm sap, fresh unprocessed coconut drinks, or similar items that could harbor contamination.

- Minimize animal exposure: Keep distance from fruit bats or wildlife. Wash hands thoroughly with soap after any animal contact or handling raw products.

- Travel thoughtfully: Consider postponing non-essential visits to active outbreak zones. Monitor health for 14 days upon return from such areas.

- Maintain hand hygiene: Regular soap-and-water washing or sanitizer use, especially after markets, outdoors, or food prep.

Quick Safe vs. Risky Fruit Guide

| Scenario | Safer Choice | Higher-Risk (Avoid) |

|---|---|---|

| Selecting at market | Intact, undamaged fruit | Visible bites, tears, or gnaw marks |

| Fallen fruit from trees | Leave it untouched | Often exposed to bats |

| Preparing at home | Wash well, peel fully | Eat unpeeled without inspection |

| Drinks from trees | Processed or boiled only | Raw palm sap or fresh unprocessed |

These quick habits add meaningful protection layers.

Building Everyday Routines for Better Defense

But that’s not all… The most effective, low-effort approach? Turn fruit inspection into a natural habit—make it a 10-second check before every meal or snack. Pair it with consistent handwashing, and you’re creating overlapping safeguards that align with how zoonotic risks are managed in endemic areas.

Evidence from public health responses shows community adoption of these simple barriers—like peeling and discarding damaged produce—helps limit transmission effectively.

If any concerning symptoms appear after possible exposure, reach out to healthcare professionals without delay.

Final Thoughts: Awareness Is Your Best Tool

Nipah remains uncommon worldwide, with outbreaks staying localized, but recent events in India serve as a timely reminder of shared health connections in our global environment. By embracing straightforward habits—especially steering clear of bitten or damaged fruit and upholding hygiene—you’re making informed, proactive choices for well-being.

Stay updated via reliable sources like the WHO or national health authorities for evolving guidance.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Where has Nipah virus been reported most often?

Primarily in parts of South and Southeast Asia, with periodic clusters in countries like Bangladesh and India—outbreaks are sporadic and not widespread.

2. Does Nipah spread easily through everyday interactions?

No—person-to-person spread requires close, direct contact with infected fluids, typically in care settings, not casual encounters.

3. Is undamaged fruit from markets generally safe?

Yes, provided it’s intact, thoroughly washed, and peeled. The main concern centers on visible animal damage or contamination signs.

Disclaimer: This article provides general information based on reports from the World Health Organization, CDC, and health authorities. It is not medical advice. Consult a qualified healthcare professional for any health concerns or symptoms.

(Word count: approximately 1320)